Description |

Mozart, Leopold (1719-1787)

|

||||||||||||||||||

Details |

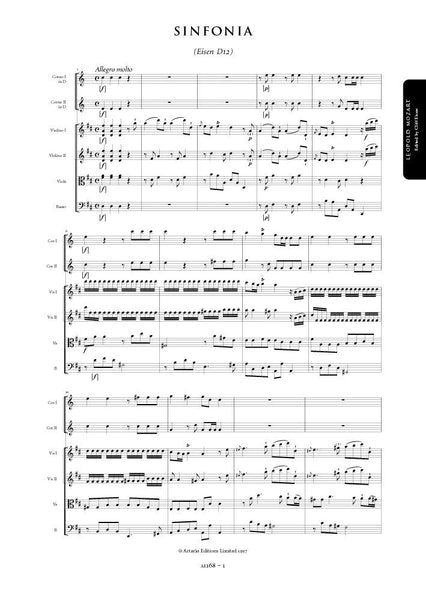

The symphony D12 (Seiffert 3.14) was composed not later than 1761. It was first advertised by Breitkopf in their non-thematic catalogue of that year and again, with incipit, in 1762. The earliest source is a set of manuscript parts of south German origin, formerly part of the Oettingen Wallerstein collection but now housed at the Universitätsbibliothek, Augsburg (shelfmark HR 4o 539); probably this manuscript dates from the 1750s. A second source, also south German in provenance, is in the Thurn und Taxis collection at Regensburg (shelfmark L. Mozart 1). Leopold Mozart had good connections at both Oettingen- Wallerstein and Regensburg; accordingly, the symphony can be presumed authentic despite the non-survival of the composer's autograph or authentic performing parts. A third source, now at the Zentralbibliothek, Zrich (shelfmark AMG XIII 7001 & a-f), is more problematic. It has no demonstrable connection to Leopold Mozart or to the 'normal' distribution of his works and the attribution on the title page notwithstanding (del Sig:re Mozart), the symphony was first attributed to Holzbauer, and then to Jomelli, in the 1813 catalogue of music holdings owned by the Zrich Allgemeine Musikgesellschaft. Furthermore, of the three sources, the Zrich gives by far the sloppiest text. This edition is therefore based primarily on the Oettingen-Wallerstein and Thurn und Taxis sources, which agree in most details. Editorial dynamics and other articulations are given in brackets; editorial slurs are dotted. No distinction is drawn between staccato dots and strokes; as his violin treatise, autographs and authentic performing parts show, only one symbol was employed by Leopold Mozart (and later by Wolfgang): the stroke, which indicates varying shades of accent and articulation, depending on the context. The only instance in which Leopold notated dots was under slurs. Additionally, slurs have not been automatically added to connect grace notes and main notes. Although Mozart's Grndliche Violinschule prescribed the universal performance of such slurs, even in cases where they are not notated, irregularities in musical orthography, changes in musical style, and the specific contexts in which grace notes appear, all suggest that this 'rule' may not have applied in numerous instances. As with most aspects of eighteenth century performance, the performance of slurs, articulation, tempo and ornamentation are subject to 'good taste'. Obviously wrong notes and rhythms have been corrected without comment. Cliff Eisen |

||||||||||||||||||

Score Preview (best viewed in full screen mode) |

|||||||||||||||||||

Once again, postal service to the USA is disrupted. Click for details close

Loading...

Error