Details

|

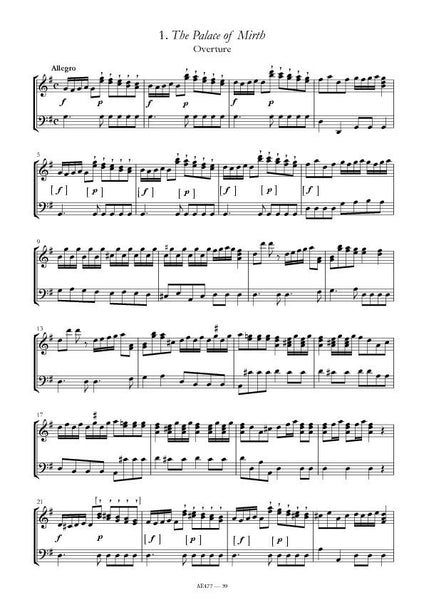

This volume has two main aims. The first is to make available what survives of the delightful and innovative short operatic works that Charles Dibdin wrote for the theatre at Sadlers Wells near Islington in the 1770s. Five of these musical dialogues, as he called them, were published in short score in 1772 and 1773, and 15 more survive incomplete. The fragments range from a complete libretto and several songs (Yo Yea! or The Friendly Tars) to a single song text (None so Blind as Those Who Wont See). I have thought it best to print what survives in a quasi-diplomatic edition, with the short scores left more or less in the same format as in the original editions, and the libretti and song texts presented with a minimum of editorial changes. This allows the user to see exactly how they survive, and to make performing versions from them to suit individual circumstances. The other option, to reconstruct Dibdins orchestration and (where necessary) vocal scoring, was successfully accomplished by Roger Fiske in the 1960s with his performing version of The Brickdust Man, though it inevitably involves more speculation and artistic licence than one expects in a scholarly edition.

The other aim is to draw attention to the wealth of material that survives for English theatre music at this period. There has been a good deal of research into Italian opera in London in recent years,2 though relatively little work has been done on its English counterparts since Fiske published English Theatre Music in the Eighteenth Century (Oxford, 1973; 2/1986). He was the first person in modern times to treat Dibdins Sadlers Wells dialogues as viable dramatic works that might be of interest to a modern audience, and his enthusiasm for them in his book provided me with the initial impetus to investigate them myself. Fiske listed eleven of them, though subsequent research, particularly by Robert Fahrner for his dissertation (published as The Theatre Career of Charles Dibdin the Elder (1745-1814) (New York, 1989)) has shown that Dibdin wrote at least 21. A search through contemporary newspapers and the voluminous Dibdin literature from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries has revealed a good deal of new material, including a remarkable series of reviews and descriptions in The Morning Chronicle. At a late stage Evan Mark Brindentines important dissertation Thomas King at Sadlers Wells and Drury Lane: Proprietorship and Management in late Eighteenth-Century English Theatre, 1772- 1788 (Ohio State University, 1997) directed me to material in newspapers that I otherwise would have missed. Appendix II is a catalogue of the surviving material relating to Dibdins Sadlers Wells dialogues. My hope is that this volume will inspire others to investigate other areas of Dibdins vast output. There is much attractive music awaiting revival, and the documentary material has the potential to contribute a good deal to our understanding of music in the late eighteenth-century London theatres. I am grateful to Ian Sapiro for putting the music into computer files for me, and to Andrew Woolley for helping me with the process of checking.

Peter Holman,Review of the Edition available from Cambridge Journals Online.

|